Channeling Chomsky: American objectives with Iran

The major risk Iran posed was setting a dangerous example of successfully operating outside the U.S.-Israeli regional order

Recently I wrote about Israel’s objectives with Iran, which are not just to remove the Islamic Republic’s ability to enrich uranium but part of a broader effort at attaining unchallenged regional hegemony (which is essentially in line with realist theory on international relations.)

But what of American objectives with Iran? Is it really as simple as “Trump was manipulated by Netanyahu and the Israel lobby into doing Israel’s bidding”?

I don’t think it was. If you step back and look at the broader pattern of behavior by the United States since the end of the Second World War, when it became a preeminent global power, there is a discernible strategy that expectedly seeks to maintain American global dominance.

Understanding that strategy is helpful context for assessing what the U.S. objectives are vis-a-vis the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Noam Knows Best

Devoted readers of Noam Chomsky’s political writings will be familiar with his elucidation of how the U.S.’s “imperial grand strategy” was a focus of policy-planners during the Second World War and driving element of the post-war institutions set up by the Allies. Chomsky has discussed this in many books, essays and lectures. Here I quote (at a bit of length, bear with me) from his 2002 book “Hegemony or Survival”:

The basic principles of the imperial grand strategy…go back to the early days of World War II. Even before the US entered the war, high-level planners and analysts concluded that in the postwar world the US would seek "to hold unquestioned power," acting to ensure the "limitation of any exercise of sovereignty" by states that might interfere with its global designs. They recognized further that "the foremost requirement" to secure these ends was "the rapid fulfillment of a program of complete rearmament"—then, as now, a central component of "an integrated policy to achieve military and economic supremacy for the United States." At the time, these ambitions were limited to "the non-German world," which was to be organized under the US aegis as a "Grand Area," including the Western Hemisphere, the former British Empire, and the Far East. After it became fairly clear that Germany would be defeated, the plans were extended to include as much of Eurasia as possible.

The precedents, barely sampled here, reveal the narrow range of the planning spectrum. Policy flows from an institutional framework of domestic power, which remains fairly stable. Economic decision-making power is highly centralized, and John Dewey scarcely exaggerated when he described politics as "the shadow cast on society by big business." It is only natural that state policy should seek to construct a world system open to US economic penetration and political control, tolerating no rivals or threats.

A crucial corollary is vigilance to block any moves toward independent development that might become a "virus infecting others," in the terminology of planners. That is a leading theme of postwar history, often disguised under thin Cold War pretexts that were also exploited by the superpower rival in its narrower domains. The basic missions of global management have endured from the early postwar period, among them: containing other centers of global power within the "overall framework of order" managed by the United States; maintaining control of the world's energy supplies; barring unacceptable forms of independent nationalism; and overcoming "crises of democracy" within domestic enemy territory… Over the years, tactics have been refined and modified to deal with these shifts, progressively ratcheting up the means of violence and driving our endangered species closer to the edge of catastrophe.

The upshot here is that the Second World War provided the United States the opportunity to reshape the world in a way that America’s economic and geopolitical interests would have the best chance at prevailing - and it took that opportunity.

A key point to drive home, and one that Chomsky explicitly states but is worth repeating here, is that it “is only natural that state policy should seek to construct a world system open to US economic penetration and political control, tolerating no rivals or threats.” That is to say, it may be easy to dismiss this strategy as some kind of baseless conspiracy theory but as any Realist Theorist would argue - any state in this position would do the same thing. It is “only natural” that a state which finds itself suddenly atop the global order would then seek to maintain that position as long as it could.

How the U.S. executes that strategy has evolved over time but has had more consistency than not. The institutions set up in the post-war period were designed, in part of in whole, to either solidify American power or contain Soviet power (the U.S.’s main geopolitical rival), or both. Think of the IMF and the World Bank, the United Nations and NATO. All served American interests in the immediate post-war period and for the most part (especially with regard to NATO, the IMF and World Bank), still do.

The Grand Arena

How the U.S. saw the global economic system has evolved as well but still maintains its basic contours, which is important to understanding why it views Iran as a problem. In the initial post-war period, the United States sought to re-establish industrial cores in Europe and Japan - in addition to the U.S. itself. The industrial cores would be supported by what would become known as the “developing world” (also referred to as “the third world” or the “Global South.”) These countries and region would supply raw materials and resources to the industrial core, while also serving as markets for surplus goods and capital. Whether or not these countries were independent of European colonial empires or not did not matter that much - so long as the countries didn’t pursue an independent path to development.

The biggest fear (and this is important) is that if any one country in the Global South successfully achieves development outside the auspices of its economically subservient role to Western power centers - then it could serve as an example to other countries who also might challenge the system. It didn’t matter if that particular country had no connection to the Soviet Union and just wanted to pursue an independent path. - what mattered is that they stay within the system.

As Chomsky notes “US planners from Secretary of State Dean Acheson in the late 1940s to the present have warned that ‘one rotten apple can spoil the barrel.’ The danger is that the ‘rot’-social and economic development-may spread.”

Hence the U.S.’s desire to see Vietnam stay part of the French Empire when a rebellion of Vietnamese nationalists sought independence. It didn’t matter that Vietnam initially sought a good relationship with the United States and not to be part of a Soviet-led empire. Thus when the French called it quits, the U.S. took over the war and bombed Vietnam (and later, Laos and Cambodia), fueling a conflict that killed between 2.5 and 4 million people in Southeast Asia.

One saw this again and again in the developing world, where the U.S. directly or indirectly intervened in a country to stop any kind of independent economic nationalism from taking hold. Guatemala, Indonesia, Chile and… most relevant for us today, Iran.

The Prize

Early on in the Second World War, policy planners in the United States realized the critical importance that oil would play in the U.S.’s victory and the importance of maintaining easy access to oil in order to solidify American dominance after the war. But how would they achieve that, especially if U.S. oil reserve eventually went dry? Daniel Yergin’s epic history of the oil industry “The Prize”, takes us right into those discussions:

Although oil was then flowing from American ports to all the war fronts, the United States was destined to become a net importer of oil - a transformation of historic dimensions and one with potentially grave security implications. The wartime gloom about America’s recoverable oil resources gave rise to what became known as the “conversion theory”, that the United States and particularly the United States government had to control and develop “extraterritorial” (foreign) oil reserves in order to reduce the drain on domestic supplies, conserve them for the future, and thus guarantee America’s security…And where were these foreign reserves to be found?

There was only one answer. “In all surveys of the situation,” Herbert Feiss, the State Department’s Economic Advisor, was to say, “the pencil came to an awed pause at one point and place - the Middle East.”

Here I risk going into a long tangent about how the oil reserves of the Middle East have been the essential factor in U.S. relations to the region since the end of the Second World War. That much is known and published in great detail elsewhere (including in Yergin’s book, which I highly recommend.

Suffice to say, controlling the Middle East was then and has been a key part of American foreign policy. And this is best summed up again by Chomsky, reflecting on the value of the region to the United States.

Control of the strategically significant Middle East, with its huge and easily accessible oil reserves, has been a centerpiece of policy since the U.S. gained the position of global hegemon after World War II. The reasons are not obscure. The State Department recognized that Saudi Arabia is “a stupendous source of strategic power” and “one of the greatest material prizes in world history.” Eisenhower described it as the most “strategically important part of the world.” That control of Middle East oil yields “substantial control of the world” and “critical leverage” over industrial rivals has been understood by influential statesmen from Roosevelt adviser A. A. Berle to Zbigniew Brzezinski.

These principles hold quite independently of U.S. access to the region’s resources, which, in fact, has not been of primary concern. Through much of this period the U.S. was a major producer of fossil fuels, as it is again today. But the principles remain the same, and are reinforced by other factors, among them the insatiable demand of the oil dictatorships for military equipment and the Saudi agreement to support the dollar as global currency, affording the U.S. major advantages.

Proxies for Power

Chomsky (and others) argue the desire to have some kind of control over the region is a major factor in American support for Israel. A pivotal point to the relationship was in 1967. The United States was bogged down in Vietnam while facing considerable domestic unrest at home. It was stretched thin and at the same time Arab nationalism - led by the most populous Arab state, Egypt - were openly challenging Western dominance and fighting a proxy war against the U.S.’s main Arab client state, Saudi Arabia.

And then, over the course of six days in June of that year, Israel launched a war and crushed the military forces of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. The face of secular Arab nationalism had been humiliated and set a course of events in which Egypt - once the U.S.’s main antagonist in the region - flipped and became a U.S. client state. It is now the second largest recipient of U.S. military aid (after Israel, of course) and firmly established as a subservient state within the American imperial system.

Of course, every so often this system gets challenged. In 2011, the Egyptian people rose up against their autocratic leader (Hosni Mubbark) and sought to establish a democracy - which they briefly did with the election of Mohammed Morsi. But this posed a direct threat to the system the United States had so carefully constructed. In short order, the U.S. backed a military coup that overthrew Morsi, a coup that was described then-Secretary of State John Kerry as “restoring democracy.”

That would be news to the Egyptian people, who haven’t had a free and fair election since. But the pipeline of money and weapons continued to flow from the U.S. to Egypt’s military-backed regime and Egypt continued to play its subservient role. If people wonder why Egypt has not only stood by as Israel conducts a genocide in Gaza but is collaborating with Israel to block aid from going to the Palestinians, now you know.

The Regional Order

Of course, there are plenty other states in the region. It’s worth briefly considering some of them.

Saudi Arabia has more or less been a U.S. client state since 1945, when Franklin Roosevelt met with King Abdul Aziz ibn Saud on an American ship in the Suez. The contours of the deal was pretty simple - the U.S. would back the House of Saud in exchange for easy access to oil traded in American dollars (important for propping up the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, and important part of American global economic dominance.) The relationship has had its ups and downs but more or less lasted.

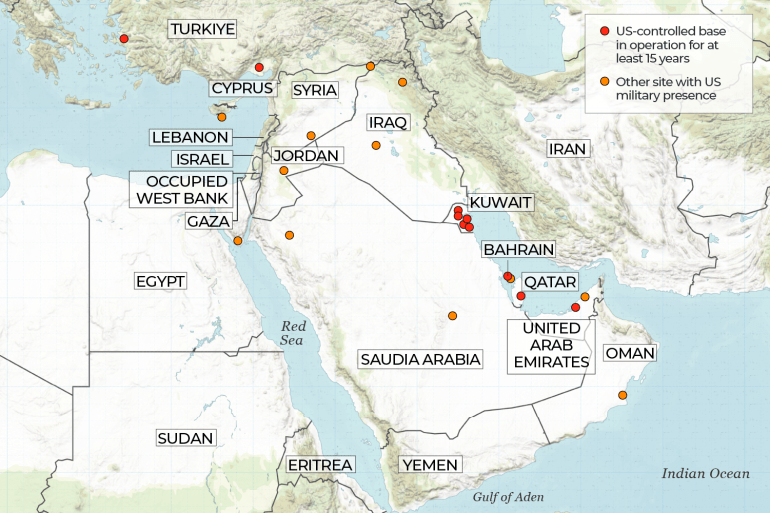

Jordan, which is run by a monarchy installed by the British Empire, signed on to be a U.S. client state when Egypt did (this is the essence of the 1978 Camp David Accords.) Most of the other Gulf states are small enough to easily be dominated by the U.S. and many of them host U.S. military bases. If any one of them gets out of line and has a popular uprising like the Egyptians did in 2011, you just have another state invade and reinstall an autocratic regime (as was the case with the U.S.-backed Saudi invasion of Bahrain, also in 2011.)

Then there are the states that did not submit to the regional framework of U.S.-Israeli dominance. States like Iraq, Libya and Syria. All three have been attacked by a combination of the U.S. and Israel in the last 15 years and had their governments replaced or otherwise turned into failed states. You could add Lebanon to that list, which has been repeatedly invaded and bombed by Israel and is a completely defenestrated state today.

For states that do submit, the rules are similar to the arrangement with Saudi Arabia. Energy-rich states must ensure a continuous supply to world markets, traded in U.S. dollars. The resulting profits must at least in part be invested in the U.S., including in American companies and through massive arms purchases. Countries must host U.S. military bases if asked (see the map atop this piece - its nearly every country) with some countries paying for the privilege of hosting the bases. They can criticize Israel in order to mollify their domestic populations but must never seriously challenge Israeli power or its project of taking over the West Bank and Gaza. And, critically, they must not pursue and independent foreign policy. During the Cold War that meant siding with the U.S. over the Soviet Union, today it means not getting too close to China or Russia.

The arrangement has made the autocratic ruling classes of these countries extremely wealthy but necessitates a heavy restriction of basic rights for the rest of the population - lest they get dangerous ideas like “democracy” in their minds. For examples of that, see above cases of Egypt and Bahrain.

The only other major state left in the region that has not subordinated itself to the regional framework is Iran. And they are a particular threat because if they can demonstrate successful independence - if they can show that it’s possible to be a strong, wealthy state that is not subordinate to U.S.-Israeli interests - then, to quote Acheson, the rot may spread to the rest of the region.

So they must be contained, or destroyed.

The Shortest History of Iran

The history of Iran (Persia) spans thousands of years, but to keep things brief, let’s focus on the modern period — a quick overview, but one that’s still full of important context.

The Pahlavi Dynasty came into power in 1925, just as the vastness of Iran’s oil wealth was becoming clear (the British incidentally had oil contracts going back to initial discoveries earlier in the century.) The Pahlavi Dynasty was led by a man named Reza Pahlavi, also known by his imperial title as the Shah of Iran.

The Shah declared neutrality during World War II, which was unacceptable to the British and Soviets, who saw it as a strategic asset that was at risk of either falling into German hands (especially after the Germans invaded the Caucasus) or at best not subordinating itself to Allied war needs. So Britain and the Soviet Union agreed to simultaneously invade and occupy Iran, which they did until 1946 (the Soviets dragged their feet on withdrawal until supposedly getting an implicit nuclear threat from Harry Truman.) The Shah was asked by the British to abdicate in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who proved to be far more compliant than his father.

Unfortunately for this new Shah, Iran was becoming something of a democracy at this time and in 1951 Mohammad Mossadegh was elected Prime Minister. Mossadegh and the Iranian Parliament were not too keen on the exploitative oil concession that had been given to the British, so they nationalized the Iranian oil industry. This infuriated the British, who asked the Americans to help instigate a coup d’etat to overthrow the Iranian democracy and reinstall the Shah (who had by this point fled to Rome) as an effective dictator. But a dictator that was subordinate to Western interests (the U.S. got 40% of a new oil consortium set up after the coup.)

The Shah ruled for the next 27 years as an autocrat, backed by a brutal CIA-trained secret police that spied on and tortured dissidents. But Iran was a pliant U.S. client state and even rewarded with help for its domestic nuclear energy program.

The Shah was overthrown in 1978 and in 1979 the Islamic Republic took hold, lead by the Ayatollah Khomeini. Iranian students around this time stormed the U.S. embassy and took its staff hostage (in part because the U.S. allowed the hated Shah to come to New York for medical treatment instead of shipping him back to Iran for trial.)

Thus ended the status of Iran as a U.S. client state and began U.S. efforts to destroy the regime. Iranian assets in the U.S. were frozen, the U.S. began to institute strict sanctions and then backed Saddam Hussein in his brutal, 8 year war against Iran. None of it succeeded in toppling the regime.

There were a few times Iran reached out to try and thaw relations, including several times in the 1990s and after 9/11. It thought the best route forward was to come to some kind of agreement with the U.S. that would end the sanctions and allow Iran to reintegrate to the region.

But each time they were rebuffed by the U.S. And there is a reason why.

The Rotten Apple - And the Nightmare Scenario of a Successful Iran

The reason the U.S. does not want to allow Iran to reintegrate into the region is that it would demonstrate that a country can successfully defy the United States and have an independent foreign policy (that is not subservient to the U.S.-Israeli dominated regional order.) If Iran can get away with it, why not Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Gulf States? Why not Egypt?

And this carries overlapping with the Israeli interest, which is to be the unchallenged regional hegemon. Both the U.S. and Israel feel that Iran, in its current state, must not be allowed to “normalize” back into the international system.

Now there is a spectrum of opinion on this matter, though a very narrow one. Under the Obama years, there was an effort to come to some kind of agreement with Iran because it was feared that if Iran continued to feel the noose tightening around its neck it would seek a nuclear weapon as a deterrent from potential U.S./Israeli aggression. Remember, Iran was suffering under an ever tightening sanctions regime that was crippling its economy and, after 9/11, saw both its neighbor to the east (Afghanistan) and neighbor to the west (Iraq) invaded and occupied by the United States - and saw many leading figures in both Washington and Tel Aviv saying the next stop was Tehran. It had good reason to feel threatened.

So Obama decided the best way to avert Iran from getting the bomb would be to have it agree to strict limitations and oversight on its civilian nuclear energy program in exchange for gradual sanctions relief. This was the “Joint Cooperation Plan of Action” or JCPOA, where Iran agreed to limit uranium enrichment to 3.67% with heavy monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency. While Obama was not completely normalizing relations with Iran, it was seeking to get past the impasse and perhaps gradually bring them into the fold so that they might just wind up turning into a subservient U.S. client state - kind of like how the U.S. flipped Egypt and Jordan after the 1978 Camp David Accords.

But this was met with hysterical outrage by both Israel and the dominant, bipartisan war faction in Washington. Although Obama was able to get the deal done, it was soon thereafter ripped up by his successor, Donald Trump, and his successor, Joe Biden, never made any serious effort to get back into it.

And it is important to understand why - because it is not completely about nuclear weapons. It is about the fear of what happens if Iran is reintegrated into the region but is not subservient to the U.S.-Israeli regional order.

Consider for a moment the following hypothetical. Iran comes to an agreement with the U.S. along the lines of the JCPOA and does not develop a nuclear weapon. Sanctions are lifted. It uses its enormous oil wealth and a flood of foreign investment, perhaps led by the Chinese, to jump start its economy. And don’t forget, Iran has a population of 92 million people. Compare that to Iraq (45 million people), Saudi Arabia (33 million people) and Israel (9 million people.) It would only be natural that freed from sanctions and leveraging its educated workforce, industrial base and stupendous natural wealth it would naturally become a dominant economic power in the region.

It would also be natural that surrounding states would be pulled into the economic orbit, signing trade and investment deals that draw them all closer together. Soon Iran is heavily investing in Iraq or Syria or Jordan. Suddenly all of those countries have a lot more stake in Iran and few it much more favorably. And it would only follow that a country with great economic wealth would direct some of that to conventional armed forces in order to secure its position.

Before long, Iran is now a regional power - and where does Israel stand? Iran’s population is 10x the size of Israel and its landmass is 75x bigger. The regional economic framework that Israel has been so carefully constructing over the last decade, where it began surreptitious trade and investment agreements with the Arab states, starts to fall by the wayside. And its complete freedom of movement, including the ability to ethnically cleanse Gaza and the West Bank - let alone its ability to invade and occupy land in Lebanon and Syria as it has recently done - starts to disappear as its no longer the unchallenged power in the region.

I don’t think there is any risk of Israel being driven “off the map.” But the risk is that Israel just becomes another state in a regional order that it no longer dominates and no longer has complete freedom to maneuver in. This is Israel’s worst nightmare.

It is a nightmare from the U.S. perspective as well. Say Iran gets closer with the Chinese, its main export market for oil. It signs all kinds of investment deals with China and perhaps hosts Chinese military bases. It ignores U.S. demands to fall in line with other geopolitical objectives - like sanctions against Russia after the invasion of Ukraine or some similar situation. It joins BRICS and doesn’t use the dollar for its oil transactions.

And - as described above - it has the other regional players start to see it is possible to operate outside the U.S. camp. Perhaps they develop closer relations with China and Russia, perhaps they start to question why all their contracts must be in dollars. Perhaps they don’t see the need to adjust their oil production levels to accommodate American economic interests.

Well now the whole thing has unraveled. The system the U.S. painstakingly set up over the course of decades after World War Two and violently reinforced has now gone to shit.

And it all happened with Iran getting the bomb.

So What’s the Plan for Iran?

Of course, it’s not a certainty any of that would happen if sanctions were lifted and Iran was able to reintegrate into the Middle East. Maybe Iran will tread carefully and recognize there are costs for stepping out of place (as every country in Latin America knows well.) But the hawkish side of the DC/Tel Aviv political spectrum do not want to take that chance.

So the plan is to destroy Iran.

This is euphemistically called “regime change,” which all the leading hawks in the U.S. and Israel have made clear is their ultimate goal. Regime change typically means what it sounds like - changing the government of a country. But no one, even the hawks, seriously think its possible for the U.S./Israel to overthrow the Islamic Republic and replace it with a more pliant government.

So instead the idea is to weaken the current government (the Islamic Republic) enough that it loses control of its own country and collapses as a state. Then outside groups funded by the U.S. and Israel (including foreign-based Iranian terrorist groups that oppose the Islamic Republic) can pour into the country and start duking it out. Secessionist groups, like the kind that could be seeded in Iran’s Kurdish population, would also be armed and funded - and encouraged to rise up against the government.

The result would not be a peaceful new government takes power. The result would be Iran descends into civil war and violent chaos. And, perhaps after Iran has been thoroughly destroyed and the population exhausted, the U.S./Israel may pick a favorite rebel group to back and take control in Tehran in exchange for subservience. This may sounds crazy… but it’s the exact scenario that unfolded in Syria - with great success. And there is every indication Iran is on that path.

The 12 Day War and What Comes Next

As of this writing (June 24), a shaky ceasefire has taken hold between Israel and Iran. But there is absolutely no reason to think this means we’re on way to a lasting peace and that Plan Iran has been set aside. It’s more likely a pause in the long game being played, which was never going to entirely consist of Israeli missile barrages.

The reason for the immediate cessation in hostilities comes at the request of the Israelis, with Western media widely reporting that Israel is quickly running out of missile interceptors that have provided a degree of protection from Iranian fire - though only a degree. Iran has also been getting in a lot of good hits and Israel is feeling the heat. But so has Israel with Iran.

So it makes sense that both sides would accept a time out. But the main issues, including the pretextual ones, are still on the table.

Israel and the Trump administration had demanded that Iran agree to give up its sovereign right to any enrichment of uranium, even for a civilian nuclear program. They also want Iran to give up its ballistic missiles program - meaning Iran would have to forfeit the very missiles it used in defense against Israel’s attack. There is no universe in which Iran agrees to those demands, which would be tantamount to a complete surrender and remove any deterrent for future Israeli aggression.

Further, early indications are that the U.S. attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities didn’t do as much damage as was initially claimed and likely only set Iran’s nuclear program back by a few months. Couple that with the fact that Iran has every incentive to now actually develop a nuclear weapon to establish some kind of deterrence from another attack - and you have a recipe for this war restarting sometime again in the near future.

What that war looks like remains to be seen - but the ultimate goal is the collapse of the Iranian state. Consider that when Israel first launched its attacks against Iran, it was by no means limited to Iran’s nuclear facilities (the pretext for the attack.) Israel attacked civilian infrastructure, assassinated a range of high-ranking Iranian officials and threatened to kill the families of others unless they fled the country. They were even supposedly close to killing the Ayatollah, Iran’s head of state. That is not a strategy to retard a nuclear program - its executing a plan to destroy the Iranian government.

Thus there is no chance of sanctions being lifted against Iran, no clear path to an agreement on its nuclear program, and there is a clear intent by Israel to achieve its ultimate goals of getting rid of the Islamic Republic, nuclear program or not.

So the covert actions will certainly be stepped up and dissident groups supported. Israel will want to take advantage of having already weakened the Iranian state. But the immediate factor is what happens with the nuclear program and if Israeli (or American) attacks resume in the next few months.

Returning to the purpose of this piece (summarizing the U.S. perspective and objectives), the main goal of the U.S. in regards to Iran was never solely about its nuclear program. It was the threat of independent nationalism operating outside the U.S.-Israeli dominated regional order. If the Islamic Republic is able to successfully defy the U.S. and be reintegrated to the global economy, it could find itself on the path to becoming a regional power that U.S. client states in the region would soon accommodate. They may soon wonder if it’s worth challenging their place in the regional order as well. Iran would also be a direct challenge to Israeli hegemony over the region and may eventually displace it as the supreme state in the Middle East, a position it has held off and on many times over the past few thousand years. American dominance in the region, dating back to its origins in 1945, would come apart.

I should note that I don’t necessarily agree with this perspective. Nor do I think it is the wisest path to take even if the goal was maintaining control over the Middle East. Not just because innate immorality and mass suffering that results from these policies but because they also put the region, the United States and potentially the globe at great risk. We could be looking at everything from the complete unravelling of the nuclear non-proliferation regime to escalation to a much bloodier, widespread and destructive conflict than anyone could imagine.

Those are the risks we face. But for some, they are risks worth taking.